There is a global epidemic of allergic diseases and Hong Kong is among the cities facing this challenge.1 At the 3rd Child Nutrition Advisory Group (CNAG) expert workshop held in July 2015 and chaired by Dr Henry Au Yeung (Paediatrician and CNAG member, Hong Kong), Professor Hania Szajewska (Medical University of Warsaw, Poland) and Ms June Chan (Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, Hong Kong) discussed current issues surrounding the prevention, diagnosis and management of allergies in children.

Prevention of early childhood allergies through nutritional interventions

Professor Hania Szajewska

Department of Paediatrics, Medical University of Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland

Editor-in-Chief

Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition

In Europe, at least 1 out of every 20 children has one or more food allergies as reported by their parents.2 The prevalence of adverse reactions to food constitutes a major health problem.2

Possible early nutritional strategies for preventing allergies include:3-8

- Exclusive breastfeeding for at least 6 months

- Use of dietary products with reduced allergenicity in infants not exclusively breastfed

- Early (versus delayed) introduction of complementary foods

- Use of probiotics

- Increased intake of polyunsaturated fatty acids

Exclusive breastfeeding for at least 6 months

According to Professor Szajewska, the topic of exclusive breastfeeding with respect to allergic disease remains controversial due to the inconsistency of results generated from studies. This is partly due to confounding factors, such as family history of atopy, parental smoking, or the presence of animals in the home. The European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) states that “exclusive breastfeeding for around 6 months is a desirable goal, but partial breastfeeding as well as breastfeeding for shorter periods of time are also valuable”.3

Exclusive breastfeeding for around 6 months is a desirable goal, but partial breastfeeding as well as breastfeeding for shorter periods of time are also valuable.

Use of dietary products with reduced allergenicity in infants not exclusively breastfed

Infants of mothers who cannot breastfeed exclusively or on a long-term basis may require supplementation with formula. Hydrolyzed formula (HF) contains broken-down milk proteins that are less immunogenic than those in standard formula (SF).9 There are two major types of hydrolyzed formulas: extensively hydrolyzed formula (eHF) and partially hydrolyzed formula (pHF). There is no consensus on the criteria for classifying formulas as eHF or pHF; however, according to industry definitions, pHF is antigen-reduced and contains oligopeptides with a molecular weight of generally less than 5,000 Daltons (Da), whereas eHF is almost antigen-free and contains only peptides with a molecular weight of less than 3,000 Da.9,10 Not all HFs provide the same degree of protective benefit10; therefore, the efficacy and safety should be established for each HF.

In a 10-year follow-up study by the German Infant Nutritional Intervention group (GINI study), the cumulative incidence of allergic manifestation from birth to age 10 years, particularly in atopic dermatitis but not asthma, were significantly decreased in infants with family history of allergies fed pHF-whey (adjusted relative risk [aRR], 0.71; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.56–0.89) and eHF-casein (aRR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.53–0.87), but not eHF-whey (aRR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.66–1.03), compared with standard cow’s milk formula.11

A cost-analysis based on data from five European countries found that pHF-whey is a feasible option for prevention of atopic dermatitis in at-risk infants that is cost-effective for public healthcare systems compared with SF.4 pHF-whey is also associated with substantial cost savings when compared to eHF.4 However, as the efficacy and safety must be established for each HF, only an HF with a documented effect should be used in infants with a high risk of developing allergies.

Early (versus delayed) introduction of complementary foods

Prospective studies have shown that avoidance of allergens beyond 4–6 months of age has either no effect or leads to an increased risk of allergies in children.12-14 A randomized controlled trial in children with severe eczema, egg allergy or both, between the ages of 4–11 months showed a significantly lower prevalence of peanut allergies in children who were introduced to peanuts early (from baseline) compared with those who avoided peanuts until 60 months of age (relative risk ratio [RRR], 86.1%; p<0.001).5

Use of probiotics

The World Allergy Organization suggests the use of probiotics in high-risk infants, as well as pregnant and breastfeeding women with children at high risk of developing allergy as there is a likely net benefit on eczema prevention; there is very low certainty that probiotics have any effect on other atopic diseases.6 However, according to an analysis by Professor Szajewska, these recommendations are based on data from only 12 different probiotics, of which only one was studied more than once. Therefore, more data is needed on individual probiotic strains before general recommendations can be made.

Increased intake of polyunsaturated fatty acids

Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFAs) have anti-inflammatory properties and have been studied in the prevention of atopic diseases. Some data show that maternal or infant supplementation with n-3 PUFAs leads to a decreased incidence of asthma, eczema and allergy while others show that there is no change at all.7,15,16 Therefore, the effect of PUFAs on reducing the risk of atopic disease is unclear and needs further study.

Antioxidants, folate and other vitamins

Thus far there have been no intervention studies on the correlation between supplementation with antioxidants or folate and the incidence of allergies. Available evidence is insufficient to support a relationship between vitamin D supplementation in infants and children, and prevention of allergic diseases.8

Summary

Exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months is the optimal nutritional strategy for all infants. Professor Szajewska recommends using only HFs with a documented effect in infants with a high risk of developing allergies. In addition, infants should be introduced to various foods at 4–6 months of age, where the delayed introduction of allergenic foods is not recommended.

Algorithms for diagnosing and managing food allergies in children

Ms June Chan

Senior Dietitian, Allergy Centre

Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital

Hong Kong

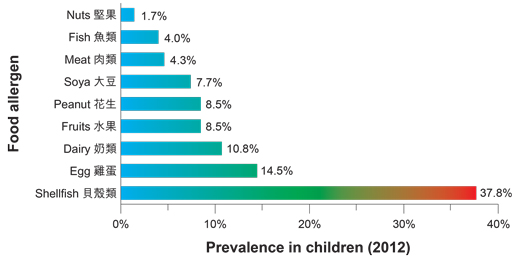

Allergies occur in two phases: sensitization and allergic response. Sensitization occurs when the immune system first encounters an allergen and starts producing immunoglobulin (Ig) E antibodies.1 After sensitization has occurred, the presence of the allergen will cause sensitized IgE antibodies to produce an allergic response which may consist of local symptoms, such as runny nose and red, itchy eyes, and/or systemic symptoms, such as wheezing, shortness of breath or anaphylaxis.1,17 Food allergens induce sensitization and allergic response through the same mechanism.1 The estimated prevalence of food allergy in children aged 0 to 14 years in Hong Kong is 4.8%;18 prevalence rates of common allergenic foods are shown in the Figure. It has been found that many children will outgrow their allergies to milk or eggs; however, a peanut allergy is generally lifelong.17

According to Ms Chan, there are often commonalities between food allergens within the same family (e.g. fish, tree nuts, grains and legumes) that can be recognized by the immune system, leading to cross-reactivity. Thus, an individual who is allergic to one type of food may also experience mild to severe allergic reactions to another food within the same family.19

Sensitivity and specificity of food allergy diagnostic methods

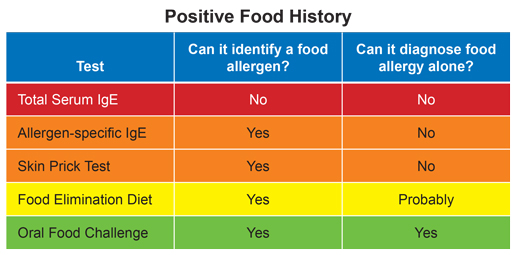

Blood tests screening for IgE antibodies and skin-prick tests are convenient means of identifying or ruling out an allergy; however, the most specific test for diagnosing a food allergy is a double-blind, placebo-controlled oral food challenge (Table).19,20 In general, the skin prick test and blood test, namely the radioallergosorbent test (RAST), both have high sensitivity but low specificity. However, various studies have established that RAST is associated with greater than 95% specificity in children for egg, milk, peanut or fish allergies in particular.20

Strategies for managing cow’s milk protein allergies in infants and children

Management of cow’s milk protein allergies requires strict dietary avoidance for 6 to 12 months, with appropriate substitution to ensure adequate nutrition before attempting to reintroduce milk.21

With milk allergies in children, decisions often depend on the age of the child and the severity of the allergy. If possible, the infant should return to breastfeeding; if the child continues to experience allergic symptoms, then the mother may also need to avoid milk.22 If the child cannot be exclusively breast-fed, it is advised to use eHF as it is tolerated by most infants with a proven cow’s milk protein allergy.9,23,24 In milk-allergic children under 6 months, eHF is the first treatment of choice.23-25 Amino acid formula is recommended for children who cannot tolerate eHF or have a high risk of anaphylaxis.23,24 Soy-based formula may be considered in children older than 6 months who are not allergic to soy protein.22,24

Summary

The estimated prevalence of food allergy in Hong Kong in children aged 0 to 14 years is 4.8%. Suspected allergies should be identified by a blood or skin prick test and confirmed by an oral food challenge. As a dietitian, Ms Chan advocates for treating allergies by strict dietary avoidance of the allergen for 6 to 12 months before trying to reintroduce the food item.

Q and A with the Faculty

Question: Studies have shown that introducing certain allergens, such as peanuts, early on can reduce severe reactions. Would you consider introducing solid food before 6 months of age?

Ms Chan: The period for safe introduction of solid food items is between 4 and 6 months, depending on the baby’s readiness to feed. The authors of the study are suggesting not delaying the introduction of peanuts, but they are not necessarily suggesting introducing them earlier [than 4–6 months].

Professor Szajewska: Regarding very early introduction of foods before 4 months of age, the ESPGHAN Expert Committee on Nutrition is not in favour of this; even if there are some studies suggesting its benefit, the data are not strong enough to support making this a policy.

Question: If a woman is planning a pregnancy, do you recommend that she avoids common food allergens during pregnancy?

Ms Chan: There is currently no evidence supporting maternal avoidance of food allergens [as a viable strategy for preventing allergies in infants].

References

1. Chan YT, et al. Hong Kong Med J 2015;21:52-60.

2. Nwaru BI, et al. Allergy 2014;69:992-1007.

3. Agostoni C, et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2009;49:112-125.

4. Spieldenner J, et al. Ann Nutr Metab 2011;59 Suppl 1:44-52.

5. Du Toit G, et al. N Engl J Med 2015;372:803-813.

6. Fiocchi A, et al. World Allergy Organ J 2015;8:4.

7. Dunstan JA, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003;112:1178-1184.

8. Della Giustina A, et al. World Allergy Organ J 2014;7:27.

9. Fiocchi A, et al. World Allergy Organ J 2010;3:57-161.

10. Greer FR, Sicherer SH, Burks AW. Pediatrics 2008;121:183-191.

11. von Berg A, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013;131:1565-1573.

12. Snijders BE, et al. Pediatrics 2008;122:e115-122.

13. Zutavern A, et al. Arch Dis Child 2004;89:303-308.

14. Filipiak B, et al. J Pediatr 2007;151:352-358.

15. D'Vaz N, et al. Pediatrics 2012;130:674-682.

16. Marks GB, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006;118:53-61.

17. National Health Service (NHS). Food allergies in children. Available at: http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/pregnancyandbaby/pages/foodallergiesinchildren.aspx#close. Accessed 24 Aug, 2015.

18. Ho MH, et al. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol 2012;30:275-284.

19. Bernstein IL, et al. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2008;100:S1-148.

20. Kurowski K, Boxer RW. Am Fam Physician 2008;77:1678-1686.

21. Ho M, Chan J, Tak-Hong L. Guideline for the diagnosis and management of cow’s milk protein allergy (CMPA) in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Institute of Allergy. 2014.

22. Vandenplas Y, et al. Arch Dis Child 2007;92:902-908.